Before I begin, let me preface this post by stating that I have no information that says definitively that the Raiders are leaving Oakland. This is mainly a thought exercise. The Raiders could conceivably leave for a new football stadium next to the existing Coliseum. They could go to Santa Clara or San Antonio for a few years before returning permanently. They could leave for Inglewood or Carson for good. In any case, this is meant to be a discussion about benefits for the A’s, nothing more. What happens to the Raiders is not under the A’s, A’s ownership’s, or fans’ control. There’s little East Bay politicians can do save for writing enormous checks to Mark Davis. So for the purposes of this post, let’s leave what the NFL and the Raiders may or may not do out of it.

—

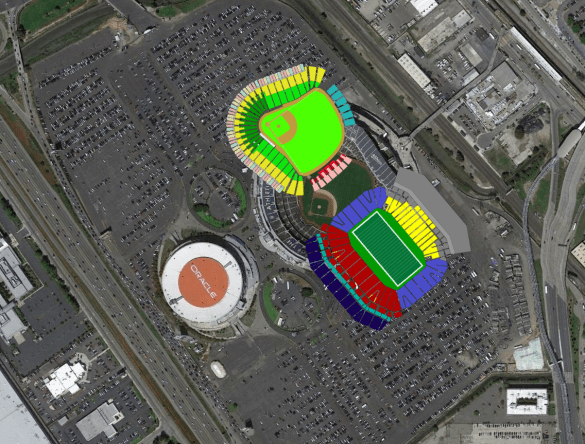

Should the Raiders leave for God-knows-where after the 2015 or 2016 football seasons, the A’s and the Coliseum JPA will have some serious choices to make regarding the old venue. The main goal would be to make the Coliseum a more pleasing baseball environment for players and fans alike, while not costing an arm and a leg to do so. The cost issue comes into play because, if we’re assuming that the A’s would pay some amount for this transformation, there’s a question of how much they’d be willing to put into this project as opposed to funneling more money towards a ballpark on the same grounds. That’s the tension at play, and when considering the various decisions that have to made cost-benefit should be at the forefront.

The immediate change we can safely assume the A’s will make is to take control of the Raiders’ locker room, one floor above the A’s current leak and sewage-plagued clubhouse. The Raiders got control of the old, 50,000-square foot exhibit hall space when the came back, turning it into spacious locker rooms for themselves and visiting teams. The A’s will occasionally use the area for hosting groups, since the Coliseum lacks proper breakout spaces at any level except for the East Side Club. Once the A’s commandeer the exhibit hall, the old clubhouse problems should go away. The old clubhouses could themselves be remodeled into memorabilia-filled bunker suites or other premium accommodations that are currently lacking at the Coli. It might cost $10-20 million to renovate the space properly, which might include moving the workout room, trainer’s room, and offices at the clubhouse level. Since all of the benefits would go to the A’s, it would make sense for them to foot the bill for the remodel.

Beyond that, changing the Coliseum could go in any number of directions.

Option A: Return to the pre-Mt. Davis Coliseum (cost estimate: $35-50 million). The frequent refrain I’ve heard so far is a call to transform the Coliseum into the pre-1995 version, with the old bleachers in the outfield and the ice plant above it. Doing so would require the demolition of most if not all of the Mt. Davis structure, plus the construction of replacement seating and landscaping. While that would be perfectly acceptable to the A’s and A’s fans, the City and County are still on the hook for the Mt. Davis debt, so the idea of spending more money on demolition and additional seats that would not generate anywhere near the requisite revenue to pay for them doesn’t sound promising in the slightest. Besides, how many years would this configuration be used? Five? I would expect all parties to pass on this plan if it were ever proposed.

Want this again? It’ll cost ya.

Option B: Lop off the top part of Mt. Davis ($10 million). The best way to bring back the view of the Oakland hills, without incurring the cost of completely demolishing and rebuilding the Coliseum, is to take down the upper part. What’s the upper part, you ask? Well, that depends. It could be as little as the upper deck, which practically starts as high as the rim of the original upper deck. Or it could include removing the upper two suite levels, making the total struck roughly as tall as the original upper deck’s lower rim. The BART plaza, East Side Club and associated seats (Plaza Reserved) could be kept around, though with the large number of obstructed view seats they’d serve a better purpose as an outfield restaurant bar, much like the kind many ballparks are instituting these days. On the downside, there would be a lot of expense just to open up the views. Again, it’s a high-cost/low-benefit situation.

Top of the original bowl is as tall as the bottom of Mt. Davis upper deck

Option C: Leave Mt. Davis as is, fill in foul territory with seats ($25 million). Given the $100 million lower deck renovation at Dodger Stadium, this seems like I’m undershooting things quite a bit. But most of the money at Dodger Stadium went towards extremely well outfitted clubhouses and a large, swanky club restaurant behind the plate. There are some structural things to address, such as dugout expansion and realignment. The bullpens might have to be moved. One way to go would be to scrap the existing lower bowl and make it more like one of the original cookie cutters, like Shea or Riverfront. Chief benefits would be more seating at improved angles, plus additional concourse space in theory. However, it would be expensive to implement and would eliminate most of the views from concourse, at least down the lines. Plus the way the concrete beams that support the Plaza level are only 4 feet above the lower concourse floor, so a concourse expansion would have to be another 4 feet lower than the existing lower concourse in order to allow for proper circulation.

An expanded concourse has its downsides and challenges

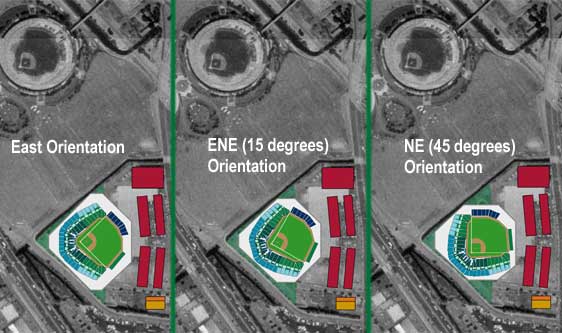

Option D: Move home plate back eight feet, bringing every seat on average 6 feet closer to fair territory ($5-10 million). Also known as the Ken Arneson plan, this proposal would sacrifice views from the Value (upper) deck in order to bring everyone else several feet closer. I like the idea of the Monster-type seats in the outfield, though I would also like to see a wholesale rework of the bleachers with steeper pitched seats if they’re going to add a premium option. That way the first row could be as little as 8-10 feet above the field, instead of the 15-foot high scoreboard wall that exists in the power alleys. While they’re at it, the metal “notch” sections that fill in either down the lines for baseball (sideline for football) should be replaced. They have a nasty tendency to pool water when it rains, and they’re more weathered than the permanent concrete sections. Changes like these certainly won’t be eye popping or easy to spell out in an offseason ticket sales pitch, but they can certainly help the vast majority of fans without incurring great expense.

—

The Giants and Cardinals both made changes to their venues as they waited for their purpose-built ballparks to materialize. In both cases, they built fan goodwill that was cashed in when their ballparks opened. Just as the A’s built new training facilities and rebuilt a ballpark in Mesa, a similar investment could pay off in Oakland. It couldn’t come until everyone knew the Raiders were leaving, so we wait. And wait.