Update 7:20 PM – Around 4:30 today, an article by the Trib’s Matthew Artz indicated that Oakland officials apologized to Lew Wolff for erroneously stating that the City and Mayor Jean Quan didn’t receive the letter. Wolff angrily replied (in ALL CAPS no less) that he did, in fact, send the letter, and later produced a letter of acknowledgment from Quan dated January 2. During the Bucher & Towny show on The Game, Townsend explained that his crew and Phoenix reporter Kevin Curran had launched their own inquiry into the status of this now mythical letter. Curran sent an email to the Mayor’s office asking for the letter since, by law, the City has to file all such communications. This afternoon the story from Artz broke, followed by an email reply from Quan spokesperson Sean Maher explaining the situation. Apparently the original email, which was also sent to numerous media, was buried in the “mountain of (holiday) furlough email” the City received. Because of this, news outlets reported on it first, giving City staff the impression that they didn’t receive it, when in fact, they did. The explanation was also a bit wishy-washy because the Mayor supposedly “eventually” received the letter, giving the impression that she didn’t receive it directly. Statements coming out of the Mayor’s office yesterday continued to press that they didn’t receive the letter. In any case, Oakland comes off highly incompetent at the very least and petty on top of it all, just because Santana decided to lash out at Wolff. That’s simply poor form. Obviously, that led to today’s apology.

—–

Monday’s much-delayed Save Oakland Sports meeting was held at La Estrellita in downtown Oakland. Though host Chris Dobbins was keen to not put City Administrators Deanna Santana and (Asst. Admin.) Fred Blackwell on the hot seat, to their credit the staffers addressed several lingering issues with some degree of frankness and a general lack of spin.

Blackwell gave an update on the state of the Coliseum City studies and EIR. The study work should be awarded in the next month, and documents should be ready by the end of the year. Because of the broad scope of the project, there will be a master plan for the 750 acres on both side of 880 and a specific plan for each side, the big focus being on the sports complex. Blackwell called Coliseum City the most dynamic project in the state in terms of size and transit access.

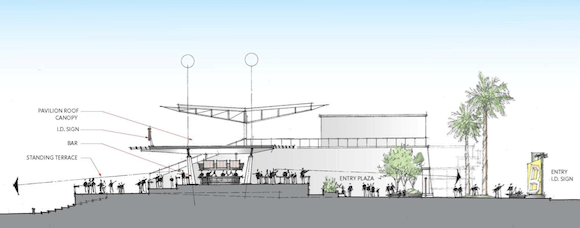

Based on JRDV’s newest renderings, he has a point. Much of the area on either side of the Nimitz would undergo a drastic transformation. While there would be a new football stadium in Lot B and a ballpark pushed up to the corner of Lot A, almost everything else would get torn down and replaced. Chief among the changes is a new arena, which would be placed west of 880, where Coliseum Lexus and another empty car dealership are situated. Low and mid rise buildings would be tightly packed from Oakport to the Estuary and in between the two stadia. Two new pedestrian bridges would cross 880. The BART bridge would be transformed into a huge plaza over the Union Pacific tracks. The only two legacy structures that would remain intact in the vision are the 12-story high-rise office building that briefly housed the Tribune and the newer Zhone building.

Before your eyes roll completely into the back of your head, let’s look at the three venues, starting with the ballpark. Blackwell continued previous talk of Oakland giving Lew Wolff information on Coliseum City and Howard Terminal, repeating Wolff’s continued rejection of both sites on financial grounds. Blackwell flat out said that new ownership may be required to get something done in Oakland, and that a MLB could act on behalf of a team to get a deal done. Of course, Blackwell cited Miami as an example of that working. “Working” meant taxpayers putting up 2/3 of the cost and politicians who approved the deal being run out of office. MLB wouldn’t do that unless it felt it could get several pounds of flesh. In Oakland, there is no flesh to take. The only thing MLB has offered so far is to negotiate the short-term lease at the current Coliseum.

As for the Raiders, Santana mentioned upfront that it took four months to get all of the right people (City, County, Raiders) named and set to negotiate the future stadium deal. Four months? You’d figure an e-mail thread and a conference call or two would take care of that.

In a refreshing bit of candor, Santana and Blackwell talked about the challenges facing the Raiders’ stadium piece. Santana said twice that any new project would have to bake in the $100 million of remaining debt (Mt. Davis). As I’ve mentioned before, any advantages Oakland has because of “cheap land” are wiped away because of this albatross. It also makes financing somewhat unclean, though that would depend on how current and future debt are structured. Right now, Mt. Davis debt is tied to the general fund of both City and County and was refinanced last summer. I imagine it could be complicated to restructure the debt to be paid solely by stadium/project revenues and would drive up the cost of borrowing to boot. Santana also talked about how the defeat of Measure B1 in November negatively impacted funding for Coliseum City to the tune of $40 million.

Blackwell admitted that the NFL may have a hard time giving the $200 million that Mayor Jean Quan is looking for, citing fan and corporate support. Why? The G-3 and G-4 loan programs are dependent on two specific revenue streams: national TV money and club seats. TV money is not that big a deal since it’s highly distributed, but the NFL is wary of teams running into blackouts. The Raiders are a particular high-risk case because even though the stadium doesn’t have a large capacity among NFL stadia, it’s had its share of blackouts and has a relatively low season ticket base (30,000). The recent tarping and pricing moves done by the Raiders are being done to grow the season ticket figure and reduce the chance of blackouts. In future seasons, the Raiders could increase capacity as the roll grows and the team performs better. Corporate support is another matter. Blackwell said that the NFL considers corporate support more important than regular fan support. The 49ers have done exceedingly well selling to businesses, which allowed the NFL to release $200 million for the Santa Clara stadium. Corporate support is not great in the East Bay, and the 49ers may have taken some East Bay business from the Raiders, putting the Silver and Black in a very tough position. Blackwell didn’t offer any answers on this, other than to say that the East Bay will have to step up to show it can support the Raiders in a new stadium. It’s a sobering but realistic view, not one to go rah-rah about.

On the Warriors front, Blackwell laid out the City’s case very plainly: Oakland would wait until W’s ownership got frustrated with the process of building something at Piers 30/32, then welcome the team back with open arms. With the A’s, ownership is certainly frustrated (with MLB and the Giants), not enough to run back to make a deal with Oakland. While working in SF, Blackwell saw the same strategy in place for the 49ers, only to see the team start building in the South Bay.

Things got a little strange with Santana laid into the A’s. Santana accused the A’s of playing games, claiming that the letter Wolff wrote requesting a five-year lease extension was only sent to the media, not to City or County. That’s rather confusing, because as the Merc’s John Woolfork wrote on 12/21:

If Wolff’s letter was discouraging to Oakland Mayor Jean Quan, she didn’t let on, saying in a statement that she was “pleased to receive Mr. Wolff’s letter stating his desire to stay in Oakland for five more years.”

Considering that it took four months to figure out who the players were in a negotiation, I wouldn’t be surprised if the letter was lost somewhere. One thing to keep in mind is that Wolff has already done two lease extensions at the Coliseum during his tenure. If there’s one real piece of stability here it’s Wolff, not the turnover in Oakland City Hall.

The tough part of all of this back-and-forth is that even if Oakland is resurgent as its supporters say it is, it’s not to the scale of SF and SJ. It may never be to the scale of SJ. That makes it easy to make a case against the future of pro sports in Oakland. Without some kind of miraculous public and/or private miracle to really boost Oakland, it’s hard to see how Oakland could get to its rivals’ level. Maybe the argument is that Coliseum City is that miracle. Oakland has had nearly 50 years to show that pro sports is an economic stimulator. There’s no reason to believe Coliseum City, even in its fully realized, pipe dream scenario, is the miracle Oakland is looking for. The track record – in and out of Oakland – doesn’t support it.

—–

More reading:

- East Bay Citizen (Steven Tavares)

- East Bay Express (Steven Tavares)

- Oakland Tribune (Matthew Artz)

Note: Look at how different the two Tavares articles are. Editors rule!