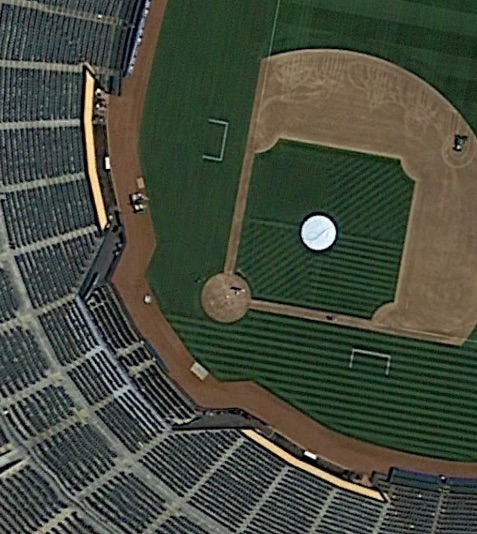

Part of the view from Section 119 is obstructed by the backstop net

During today’s A’s broadcast, the between-pitch conversation turned to netting and foul balls. New part-time color commentator Eric Chavez provided an anecdote from during his career. He was hitting batting practice at Boston’s Fenway Park, when a ball he hit went into the stands, hitting a child. Chavy found out that the child had subsequently needed five eye surgeries.

Boston became a focal point of safety when parts of Brett Lawrie’s broken bat ended up in the third base stands, hitting a fan in the head. Tonya Carpenter suffered life threatening injuries, but was eventually released from the hospital. Another fan who was hit by a ball while in the usually glass-protected EMC Club decided to sue the Red Sox last week. The glass had been removed for renovations.

Baseball is unique among all major professional sports in that it is the only sport in which the object of play (ball) routinely travels into the seating area. Most are balls hit into foul territory, with some going out in fair territory as home runs or ground rule doubles, or sometimes the occasional errant throw. For many fans, the souvenir ball is a treasure, a real achievement. For others, the foul ball is a source of potential danger. Bats present an even more perilous, albeit less frequent, hazard.

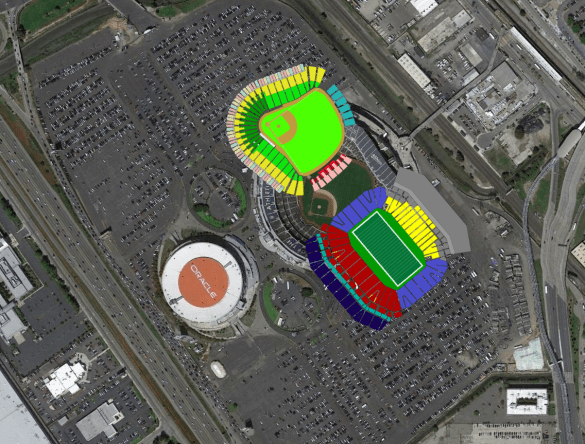

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

These accidents and their often horrific severity have caused MLB to consider changes to ballparks to increase safety, counter to the so-called “Baseball Rule.” The Baseball Rule stipulates that stadium operators can’t be held responsible for injuries caused by stray balls or bats. Over time lawsuits have whittled away at the rule’s strength, to the point that teams have to be much more cognizant of the risk than ever before. Yet little has changed to protect fans. Right now backstop nets generally cover about sixty feet behind home plate and little else. At the Coliseum, the net is full height at the back of the notch, with additional netting angling down towards the front of the notch. The dugouts and field boxes are completely exposed. Only seats at dugout level (sunken below the field) and dugouts at new ballparks tend to be protected. Everything else is typically exposed.

The threat to baseball became more pointed when Gail Payne, an A’s season ticket holder, filed a class action lawsuit against MLB over the threat to fan safety. Never mind that a winged fruit bat has more chance of reaching Payne’s seats than one of Lawrie’s maple bats, there are still plenty of safety issues that MLB has neglected for far too long. A ball coming off the bat can reach the first row behind the dugout in every ML ballpark in one second. 1,750 fans are hit every year, the vast majority in foul territory. The lawsuit asks for new protective netting to be installed from foul pole to foul pole, covering all of the front row seats in foul territory.

A foul line drive could reach these seats in less than two seconds

MLB is certain to fight that as much as it can, reasserting its Rule to some extent. To do so would severely impact views for the high-paying fans next to the field. At the same time, they have to be ready for a compromise solution. One that has been discussed recently is an extension of netting to the far edge of each dugout. That should cut down on a number of injuries, though there would still be concerns about fans farther down the lines.

Considering that Lawrie’s bat brought all of this to a head, it’s worth mentioning maple’s role in all of this. Maple bats have long been known for their greater power thanks to the wood being harder than ash. The downside of the maple bat is its tendency to shatter, creating wood shards that fly around like shrapnel, hitting fans and players alike. If it came down to banning maple bats or extending nets, MLB would most likely choose the latter, since the loss of maple bats could have a negative effect on offense.

The increasing role of technology is also a concern, particularly the use of smartphones and tablets during the game. As I sat in the seat pictured above for the A’s-Dbacks game last weekend, I constantly reminded myself to pay more attention to the game. That was a complete failure as I routinely looked down at my Twitter app, putting the phone away only when I was eating (another type of distraction). Going to the other end of the spectrum, it wouldn’t hurt to have a glove on in case something happens. Then again, if the A’s defense is having trouble fielding balls, how much can we expect of fans?

College and amateur facilities have taken the safety net a bit further than the pros have gone, covering some of their small ballparks in nets. Tony Gwynn Stadium at San Diego State University has nets that extend several feet above the railing along the front row.

Is this a bad view because of the net?

Other parks have a small extended railing, maybe a foot high, above the dugout. The fact is that there’s no proper standard. Factors other than safety can also come into play. The Yankees had difficulty opening the new Yankee Stadium when they had to balance the safety concern with the visual effect of the backstop net on the home plate camera during Yankees broadcasts on the YES Network.

MLB has plenty of data on injuries to institute new standards at current and future ballparks. They’ll have a couple chances to effect change at their two offseason owners meetings, where the safety issue should be a hot topic. Several teams are ready to extend the nets, provided that MLB enacts new standards. The cost should be minimal, in the low five-figures per ballpark. If MLB truly cares, they’ll act quickly by extending the nets instead of creating a task force to study potential changes. Some foul balls will go away, along with the combination of danger and excitement that being exposed entails. It’s worth the sacrifice to reduce the number of injuries.

—

P.S. – Part 2 will cover railings and their associated risk.