Lew Wolff brought up the the idea of a temporary stadium to the SV/SJ Business Journal’s Greg Baumann this week. Wolff looks at the concept as potentially necessary if another extension at the Coliseum can’t work out. He had already expressed concern when MLB pushed the Coliseum Authority (JPA) into a two-year extension through 2015. The thinking in November was that no new permanent home could be built in that two-year span, and if Coliseum City’s phasing and the Raider owner Mark Davis’s preference of building on top of the current Coliseum footprint take hold, the A’s would no longer have a place to play. Combine that with Larry Baer’s comments about allowing the A’s to play at AT&T Park while an Oakland solution was being hammered out, and you can see all of the moving pieces and the complexity therein. Because of that complexity, let’s break the situation down into its basic components.

To start off, there’s the Raiders. The Raiders are the first domino here, because they are the team in some sort of negotiation with Oakland and the JPA. Even though Davis has labeled the talks as discouraging recently, reports coming out of the Coliseum City partnership should bring everyone back to the table in the next month or so. Then Davis can decide how to move forward: either partner in Coliseum City, or decide that CC doesn’t pencil out and look elsewhere. So far Davis has stuck with the idea that the Coliseum is the #1 site. That could change quickly as the numbers are released and parties have to make fiduciary commitments.

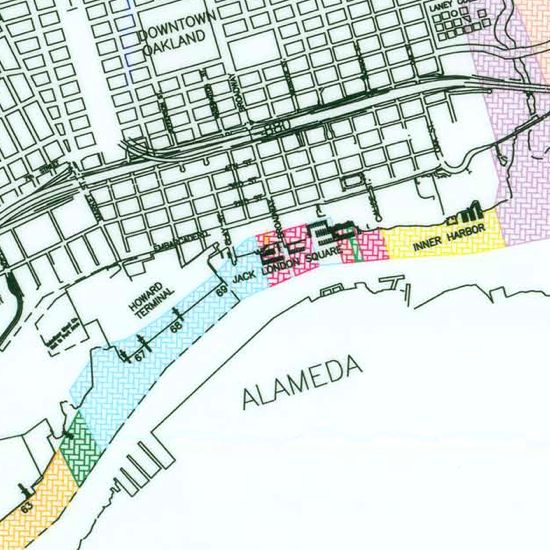

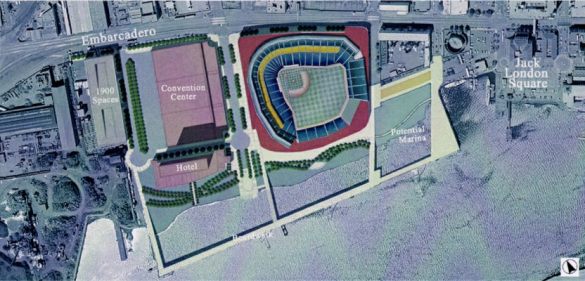

The A’s can’t do anything without the Raiders’ move. As much as Oakland waterfront ballpark proponents would love for Howard Terminal to become the apple of Wolff’s eye, the many questions and doubts that hang over the site continue to make HT a nonstarter for Wolff. Coliseum City had the A’s in a new ballpark no earlier than 2022, unacceptable terms for Wolff and MLB. However, if CC falls apart for the Raiders and Colony Capital, the Raiders could leave for Santa Clara, LA, or elsewhere. Wolff could easily call for CC to dissolve and put together a development plan of his own at the Coliseum, one that he would control. It could make room for the Raiders as well, but the football team would end up on the back burner, not the A’s. If Davis were to stay for several years at Levi’s Stadium while gathering up the resources to build anew in Oakland, such phasing could work out. Then again, the Jets spent nearly two decades “temporarily” at the Meadowlands while not working out any new stadium deal in the five boroughs of New York City.

Next, this idea isn’t new. Wolff floated the temporary venue concept in 2012, when he initially tried to get a lease extension. Wolff has reason not to go down such a path due to the expense and amount of upheaval. Should lease talks once again turn difficult, a temporary move becomes more a value proposition than a logistical problem.

If the JPA couldn’t come to an agreement on a new ballpark with Wolff – say, for instance, the JPA chose not to eat the $100 million left in Mt. Davis debt – Wolff would likely go back to MLB and again ask for a decision on San Jose. San Jose brings about one of two temporary ballpark scenarios. The first comes if the A’s are left homeless after 2015 and MLB somehow allows the move south. That’s a long shot at best, but can’t be completed discounted. In this case a temporary ballpark would have to be built somewhere in San Jose for 2-3 years minimum while Cisco Field was being built at Diridon. Besides the process of getting league approval, a temporary site would have to be found. In the Bizjournals article, San Jose Mayor Chuck Reed claimed that multiple temporary sites were available. In all practicality, there are probably only two sites. Many of the previously studied permeant ballpark site candidates are either in the process of being redeveloped (Berryessa, North San Pedro) or face logistical hurdles that make it difficult to ensure that 20-30,000 people could make it in and out easily (SJ Fairgrounds, Reed & Graham cement plant).

Instead, there will probably two or three sites in play: the old San Jose Water Company site near SAP Center (site owned by Adobe), the spare parking lot south of SJ Police headquarters between Mission and Taylor Streets (a.k.a. the Cirque du Soleil lot), or the land adjacent to the under construction Earthquakes Stadium (under control by another developer). The SJWC/Adobe site would be the easiest to convert for a ballpark, is the right size, and has an existing building that could be leveraged for ballpark use. It’s also directly underneath a San Jose Airport landing approach, which could cause red flags by the FAA. The Cirque lot is smallish, though large enough for a small ballpark. There’s lots of parking nearby, and potential makeshift parking on the other side of the Guadalupe River. Light rail is only 2 blocks away. As for the Earthquakes Stadium-adjacent site, there were enough problems getting it prepped for that project that it should give pause to anyone considering even a temporary ballpark there.

That’s not to say that San Jose is the only place for a temporary ballpark. Wolff was quoted as looking at the entire Bay Area:

“I am hopeful of expanding our lease at the Oakland Coliseum for an extended term. If we cannot accomplish a lease extension, I hope to have an interim place to play in the Bay Area or in the area that reaches our television and radio fans — either in an existing venue or in the erection of a temporary venue that we have asked our soccer stadium architect (360 Architecture) to explore. Looking outside the Bay Area and our media market is an undesirable option to our ownership at this time.”

The East Bay is in play for both temporary (if needed) and permanent venues. MLB won’t hand over the South Bay to Wolff, yet MLB has also allowed Wolff to enter agreements with San Jose, so it’s clear that MLB is hedging big time. A temporary ballpark could be built on the old Malibu/HomeBase lots near the Coliseum, in Fremont, or even Dublin or Concord. Fremont’s Warm Springs location could enter the discussion again because the Warm Springs extension is scheduled to open in 2015.

It’s also possible to read into Wolff’s statement the possibility of the A’s playing at Raley Field on a temporary basis, since his description of “area that reaches our television and radio fans” covers CSN California and the A’s Radio Network.

Warm Springs could be in play because CEQA laws that govern environmental review largely don’t affect temporary facilities. Generally, seasonal installations such as carnivals or circuses that don’t create any permanent environmental impact are exempt from CEQA. The challenge, then, is to create a temporary ballpark that can also fit this model. That would be tough because of the large-scale consumption of water, food, and energy during a single game. Still, the A’s are already familiar with major recycling efforts, and if trash can be properly contained there should be little permanent impact. Just as important, Warm Springs remains within the established territory, so MLB wouldn’t have to negotiate anything with the Giants. Finally, if the experience is positive it could provide enough political goodwill to convince Fremont to again consider being a permanent home.

Strategically, the Baer vs. Wolff war of words (what happened to the gag order?) has only gotten more interesting. Baer’s statement is cajoling Oakland, not Wolff, to get its act together. Wolff’s response is to say that the A’s don’t need the Giants’ help, especially if he can get San Jose. Keep in mind that if Oakland fails, the East Bay as a territory loses value, hurting Baer’s argument and supporting Wolff’s. What’s left is for both rich guys to let the processes in Oakland and in the courts play out, and prepare for next steps. At some point, the leagues are going to ask Oakland to either step up or step out ($$$). While some local media types continue to believe that the teams can carry on indefinitely at the Coliseum, at some point the conflicts become too great to bear. For those of us who have been following this saga for so long, it’s good to know that actions are being taken to make new homes for the teams. Even if one of those homes is temporary.