Revenue sharing is one of the bigger, yet less understood, items that comes up every time there are CBA negotiations. Since it’s mostly about how teams deal with one another, it’s not a particularly sexy topic. Yet it’s just as important as anything else, since the arguably biggest issue over the last 10-15 years has been how to address the economic disparity between small and large markets.

The A’s are in a gray area as far as how teams are defined. Oakland is considered a part of a large market, but the franchise is hampered by an outdated stadium that hampers their ability to generate local revenue. Some have called the A’s a small market because of these conditions, others call the stadium an excuse to operate on the cheap. I prefer to call the A’s low revenue since it’s an acknowledgement of both the A’s current position and the potential for when a new ballpark occurs. How the A’s and MLB planned to address the franchise’s revenue position and how both failed to execute have led us to this point. That point, for all intents and purposes, is a reset.

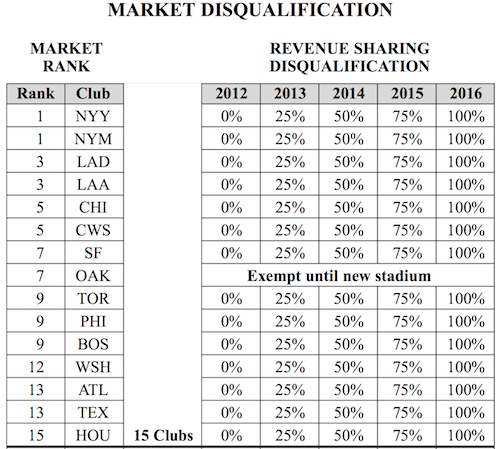

To understand why that’s the case, it’s important to know what the climate was like going into the 2011 CBA negotiations. Like the 2006 talks, there was little drama and no major items to discuss. There were tweaks to the draft and compensation system, drug policy, and to revenue sharing as well. Thanks to teams’ expanding media deals and the continued construction of new ballparks, there were few disagreements between MLB and MLBPA as everyone was getting paid. Lew Wolff and John Fisher were well into their plans to move the A’s to San Jose, having released renderings and commencing talks with the City of San Jose more than a year prior. Bud Selig appeared to be working to arbitrate the territorial rights fight between the A’s and Giants. MLB and the owners, knowing about the A’s plans, tacitly approved them by writing into the CBA a schedule to ease the A’s off revenue sharing. I referenced it in the last post.

Wolff’s San Jose plans stalled, then fell apart with a lawsuit launched by the City of San Jose failing to sway The Lodge, leaving the franchise to head back to Oakland with no other clear choices for a ballpark in their East Bay territory. The A’s three-year run of success coincided with the beginning of the CBA. The final two years were marked by a selloff of veterans and the recent tanking regime. Some looked at the recent years as little more than profit-taking by Wolff while the A’s on-field product languished. I’d rather look at it as the Beane tendency to sell early. However many teams resented the A’s (cough*Giants*cough) for supposedly pocketing the revenue sharing checks, it wasn’t enough to change how the A’s would be treated under the new CBA. The new disqualification system is the exact same formula as last time. What I was worried about was the A’s getting cut off cold turkey, which would’ve raised serious economic difficulties for the franchise going forward. It’s not so much about setting the budget, it’s about what would happen if the A’s had another magical season like 2012. If they wanted to get a rental, the ownership group would have to dig into their pockets as part of a cash call to pay for a trade. Unlike the high revenue teams with huge season ticket and corporate bases, the A’s don’t get $150-200 million up front every year to pay for everything. Even if revenue sharing continued indefinitely, the check comes when MLB completes its annual audit after the end of the season, so they couldn’t use it for in-season moves if they wanted to.

What happens now that the revenue sharing scheme from the last CBA has carried over into the new CBA? There’s talk of greater urgency to build in Oakland, a sentiment supported by A’s officials including new team president David Kaval. But if the disqualification schedule is the same as five years ago, why wasn’t there talk of urgency back then? Did people not consider the ramifications if nothing got built? Did some expect San Jose to happen with less resistance? I know I did. There is a great sense of renewed optimism in Oakland, and early indications are that Mayor Libby Schaaf will provide real material support for the A’s instead of the posturing of her predecessors. However, with the plan now limited to Oakland, the circumstances can now be considered a new ballpark in Oakland, or bust. The logic is quite simple: the A’s have no other options. I really hope the A’s get a deal done in the next two years, because I personally don’t feel any more secure about the A’s future than I have before. If the A’s encounter more difficulty and Oakland has trouble getting out of its own way, MLB and Commissioner Rob Manfred will stop playing Mr. Nice Guy and they will ratchet up the pressure on the A’s and the City. Baseball is nearing peak TV-revenue, so they will look at other ways to grow the pie. Yes, that could mean moving the team to a different market. I still don’t think contraction (which would include the Rays) is in the cards given the optics of it, but I wouldn’t put it past Manfred, who was a lead negotiator for the 2001 CBA talks, the last time the threat of contraction loomed. Let’s all hope we never get to that fearsome point.

—

P.S. – Sometimes I wonder how much the A’s stature within the Lodge would’ve been improved if they didn’t trade Josh Donaldson and Yoenis Cespedes. If one of the problems with the A’s was their cheapskate tendencies, would simply having a larger payroll by retaining key veterans have changed the detractors’ views of the A’s? Or was it more about the fundamentals of the A’s not making progress of the stadium, even though many within the Lodge actively blocked the A’s efforts? It should be the latter, though the former came up frequently in news reports.

P.P.S. – The A’s revenue sharing check is speculated to be some $34-35 million. The A’s gate revenue, as reported by Forbes last year, was $43 million. Kaval will have to work some magic to make up for the lost revenue sharing at the existing Coliseum.