Like clockwork, the annual Forbes MLB valuations roteere released yesterday, just prior to the start of the regular season. Unlike last year (which I didn’t bother to write about), there were several surprises. The biggest was the Giants’ 100% boost from $1 billion to $2 billion, on the strength of the team’s third World Series win and development potential at Mission Rock.

The other surprise was the huge gains for small market teams, led by the Royals, Indians, and yes, your Oakland Athletics. Forbes awarded the A’s a 46% gain, from $495 million last year to $725 million this year. While many revenue-related factors are responsible, Forbes also chose to up its revenue multiplier in determining the valuations, which had been falling behind actual sale prices in what has been over the last several years a hot seller’s market.

Higher enterprise ratios are being fueled by the stock market’s six-year bull run (which has inflated asset values and created a lot more buyer than seller of teams), baseball’s unmatched inventory of live, DVR-proof content, real estate development around stadiums, higher profitability (which reduces the need for capital calls) and the incredible success of Major League Baseball Advanced Media, the sports’ digital arm that is equally-owned by the league’s 30 teams.

Even the new A’s valuation may be behind the teams a bit. When Bloomberg released its own independently derived valuations after the 2013 season, then-PR man Bob Rose suggested that the number was closer to $700 million based on revenue. Before franchises started going for insane amounts, it was common for franchise owners – including Lew Wolff – to claim that Forbes’ numbers were incorrect, overselling certain aspects of a franchise’s operation. Now we’re starting to approach $1 billion for a team that has at best average TV/radio deals and no new stadium. A 300% return in a decade is pretty impressive, no matter how slice it – though Wolff and John Fisher can’t realize that until they sell the club. They’ve shown no indication that they’re interested in selling, despite how much the stAy crowd clamors for it.

As nice as the new valuation looks, it’s miles from where the Giants, Dodgers, and almighty Yankees ($3.2 billion) are. The Bronx Bombers recorded more than $500 million in revenue last year, confirming a quote from an unnamed Yankee exec in the fall. The luxury tax was designed to dissuade teams from profligate spending, but until recently that hasn’t stopped the Yankees and the Dodgers don’t seem to care one iota about the luxury tax. Redefining luxury tax penalties may become a sticking point in the next CBA negotiations, one that goes hand-in-hand with shifting the revenue sharing model for lower revenue (small market) franchises.

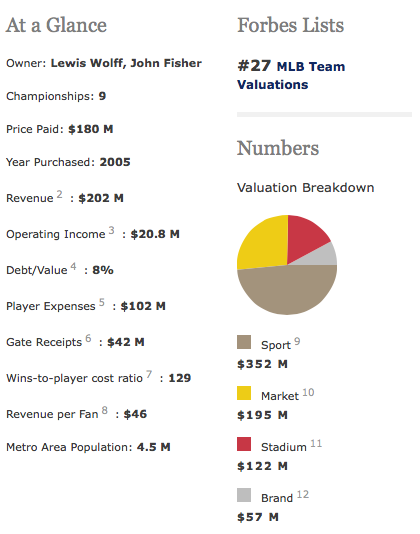

Let’s do a deeper dive into the Forbes figures. First the A’s:

Forbes breakdown of the A’s valuation

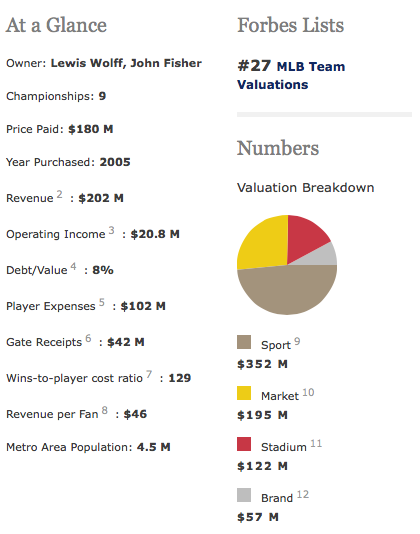

Now the Giants:

Forbes’ Giants valuation

In nearly every key measurable, the Giants double or even quadruple the A’s. The Giants hit a perfect storm of on-field success and savvy management, which was parlayed into impressive revenues. The Giants are a money-making machine. They are also a big market club, no doubt. Though they aren’t profligate spenders in terms of payroll, everything else about them is big market, just like the Yankees, Dodgers, and Red Sox.

The A’s, on the other hand, bear all the marks of a small market team. Gate revenues are abysmal compared to the Giants. It’s so lacking that the A’s could untarp all the regular upper deck seats, sell out the entire season, and still only reach 50% of the Giants’ revenue. The flipside to that is that the A’s are a far more affordable, accessible product for baseball fans in the Bay Area. The market itself, which is defined as the East Bay, compares to a lot of other small markets like Tampa Bay and Kansas City. As long as the A’s are pigeonholed to the East Bay, it’s likely they’ll remain small market, or perhaps boost themselves to a medium-sized market if a new stadium comes.

New and improved national media revenues are the tide that has lifted the A’s boat. As big market teams keep getting bigger and bigger annual revenues, the A’s will continue to be a club that receives a nice revenue sharing check, at least as long as they play at the Coliseum. Per the current CBA, they’ll continue to be eligible for revenue sharing until they start playing in a new Bay Area ballpark. So the A’s are in a sort of limbo in which right now they’re considered a small market team in that they receive revenue sharing, but will be redefined as a big market team once they open a new park. That arrangement could continue into the next CBA, or it could change. I suspect that if the A’s build a new park in Oakland, they’ll remain a small market team by definition, simply because they don’t have the same direct access to big sponsors as they would in San Francisco or San Jose.

The other big takeaway from the valuation news is that the A’s debt position has significantly improved from doing nothing. Forbes reports that the A’s debt is now 8% of franchise value, or around $60 million. That leaves an astounding $665 million of equity for the ownership group. Wolff has suggested that he would use equity to help finance a ballpark. He could conceivably cover the entire cost with the team’s equity, but MLB rules about debt load preclude such a plan. The most debt the A’s can accrue without running afoul of MLB is 12 times their operating income if they’re building a new ballpark, 10x if not. If you take the average of income from the last three years you get $25 million. Multiply that by 12 and you get $300 million. The A’s have $60 million of existing debt, but according to MLB rules they can exempt $40 million of that. Combine all of those together and the A’s can in theory finance $280 million of a stadium. Even with the added debt, chances are that by the time the stadium opens it would hit only 35-40% of the franchise’s value, an acceptable amount for a sports franchise.

Naturally, the problem is servicing that debt. $280 million over 30 years at 4% is $16 million a year. To ensure that gets covered and it doesn’t have a deleterious effect on payroll, the A’s would have to get 30-32,000 average attendance per game for several seasons, at much more expensive prices than the Coliseum to boot. Then there’s the combination of suite sales, sponsorships, and maybe even seat licenses if fans are willing to invest. If this sounds similar to what the Giants did, that’s because it is. Maybe there’s a real estate component that can come in to offset that debt service requirement, but Wolff indicated in recent comments that grand development concept such as Coliseum City is not forthcoming from him.

Nevertheless, if Wolff and Fisher want to build, and fans are willing to pay, the path is there. Getting to a deal is the hard part.

—

P.S. – Speaking of getting to deal, there’s been some noise about wanting Wolff to show his plans. Show a rendering, something to indicate that he actually wants to build in Oakland. To which I say – come on. He just finished opening a soccer stadium, the spring training facility renovation, and is finishing scoreboards at the Coliseum. Are those not indicators of wanting to build?

All of these sentiments, while well-placed, are based on some unrealistic expectations. Fact is that the stadium development process is dog slow. It’s tedious. No premature release of renderings will do anything other than getting a small handful of fans excited. Believe me, I’m one of them. But I’ve also learned over the years is that all of that is sizzle, not steak. If you want real progress, you need rules. You need a framework. Here’s the “framework” for the A’s right now:

That’s not a framework for anything other than random discussions between the A’s and East Bay pols. If the A’s, City, and County are going to work on an actual deal, they need to establish a real framework for talks and for a stadium/development deal. It would help if Oakland or the JPA started by creating an RFP (request for proposal), that would allow the A’s to formally propose something. The A’s are in the process of hiring a person to interface with City/County/JPA. If the Raiders wanted to present their own vision, the RFP could accommodate them too. That is how the Coliseum City process started, and is the proper – not to mention legal – way to do government business. Frankly, I’m past renderings. I want steak. You should too.