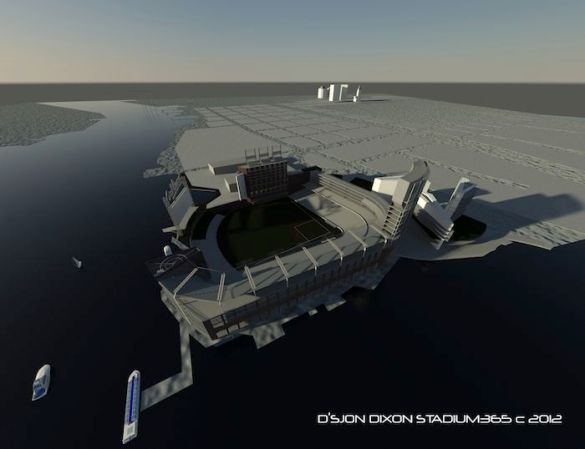

If someone – anyone – discovers a ballpark site is being discussed or presented, and he lets me know about it, I’ll take the time to cover it. Even though ownership is only focusing on one site and the City of Oakland has its own two sites in mind, it doesn’t hurt to be open-minded about others. We may find the best of breed or dismiss something entirely. Either way we’re getting educated and informed about it. I enjoy covering it, and I hope you enjoy reading about it. That brings me to the Estuary Waterfront Project, a ballpark concept by Oaklander D’Sjon Dixon. Dixon, a native East Bay guy by way of the University of Wisconsin (as he pointed out, like Bud Selig and Lew Wolff), is an excellent artist and has some brought some fresh thinking to the often static world of stadia. During his segment on A’s Fan Radio, Dixon frequently talked about his ballpark’s goals of sustainability and its ability to enhance both the waterfront and the city.

D’Sjon Dixon’s Estuary Waterfront Project would place a ballpark on the site of Estuary Park and the Jack London Aquatic Center along the Embarcadero in Oakland

Over the years Estuary Park has aroused curiosity about its ability to work as a ballpark site. It’s located east of Jack London Square, across the tracks from Victory Court. I’ve gone there multiple times and several people have asked me about it over the years. My immediate answer to them is that it’s too small. The park measures roughly 400′ x 240′ plus some estuary frontage of varying width. The Jack London Aquatic Center, which opened in 2001, is a somewhat triangular piece of land that’s also 400′ long and 300′ wide at its widest point. JLAC has a boathouse with a community room that can be rented out for events. Rounding out the landscape is the old Cash and Carry warehouse, which the City bought through its old redevelopment arm a few years ago. That parcel, including a parking lot, measures 440′ x 340′. In all, the land (which is all city-owned at this point) totals just over seven acres.

Overhead picture of Estuary Park, the Jack London Aquatic Center (bottom right), and the vacant Cash & Carry building. Yellow line across field represents 400 feet.

It’s not small just because of the acreage, it’s small because of a single dimension. In the picture above, the yellow line represents a reasonable buildable width including mandated setbacks and easements for the water and the apartment complex to the west of the land (top). 400 feet is simply not wide enough to hold a ballpark. A grandstand including the concourse will measure around 170 feet deep. Add to that 50 feet from the first row to home plate, and then at least 300 feet for a short porch to right field, and the ballpark becomes 520 feet wide. There simply isn’t room for that kind of structure on the land, unless you do something unorthodox.

To address this, Dixon took two unorthodox approaches. First, he disregarded the Estuary Park limitations and simply built more of the ballpark out into the water. I didn’t notice this until I saw more images on the project website. Notice the second pic’s taper from JLAC to the park, and how that no longer exists with the ballpark. Anyone who has spent any time reviewing CEQA knows that building anything new over what is currently water is for all intents and purposes forbidden in California. Even the Warriors arena is getting a great deal of static for aiming to build on piers, which of course aren’t land. Additional creation of land in the Bay, regardless of purpose, practically requires an act of god to make it happen. Remember the plan to extend SFO’s runways a decade ago? That would’ve required bay fill. It died on the vine. A similar effort for this ballpark, even if it required only a 100′ x 400′ slab (1/2 acre), would be laughed out of committee or ripped to shreds by Save the Bay, Waterfront Action, or the BCDC if it ever got that far. The Bay is what makes our region distinct, and people and groups have shown that they’re willing to defend it endlessly and to the death. The other unusual step Dixon took that baseball fans noticed is that he oriented the ballpark west-southwest, so that it would face JLS, Alameda Point, and in the distance, San Francisco. As we’ve discussed several times, MLB prefers its ballparks to face east or northeast. In some instances such as domes it’s willing to have a ballpark aimed north or south. This is to ensure that the sun isn’t in the batter’s eyes during the day and to provide relatively predictable shadows during the season. Interestingly, Dixon tried to address this by placing an eight-story hotel tower in right field and a big scoreboard in center. Those measures will only work in certain sun-sky conditions. The ballpark could be re-oriented southeast to fix the sun problem, but it would take away from the view. Dixon couldn’t say what the ballpark’s capacity was or explain how much onsite parking would be there. The size of the ballpark would be “up to the developer”, though he also claimed he knew three people who could fund the ballpark. It all adds up to someone who has some great ideas and understands LEED, but knows next to nothing about CEQA. CEQA is the set of regulations that forces environmental review and places restrictions on what kinds of projects can be built in sensitive places. CEQA has led rise to hyper-NIMBYism in California. On the flip side, it has allowed our coasts to remain mostly in the public interest and not full of high-rises and private development. If this ballpark concept ever got off the ground, it would immediately have Bay and waterfront activists, open space and parks preservationists, boating enthusiasts, residents of the nearby apartment complex, and many others lined up to take it down. That doesn’t include the normal anti-stadium types or additional complications such as the PUC and other governmental agency interactions. This is the stuff that Lew Wolff talks about when he says that people can’t just point at a site and say that’s a site. There’s a ton of legwork that has to be done on each proposed site, and even more on the sites that actually get studied as alternatives. There are studies of noise and shade, seismicity and hydrology, cultural and paleontological resources, along with the more common traffic and transportation work. It’s a significant, seemingly endless amount of work, and the crazy thing is that a draft version of an EIR has not been finished for any ballpark site in Oakland: Victory Court, Howard Terminal, Coliseum City, this site or any other site. And it’s telling that Estuary Park, despite its rather prominent position where the Estuary meets Lake Merritt Channel, was never really considered a ballpark site in the past. That’s largely due to all of the issues identified in this post, and probably many more that I haven’t covered. Just a thousand feet across the Channel, HOK studied two sites at the Oak-to-Ninth (O29) site in 2001. That’s not to say that Dixon’s in the wrong. He has some great ideas, and the fact that he put he put his visual skills to use in fleshing them out can help a lot in terms of creating a real vision for Oakland going forward. If the concept ultimately serves as a catalyst, it would be incredibly productive for fans who want an Oakland ballpark and need a unified rallying point. This idea can be moved and modified to work at other sites. Dixon seems to like Coliseum City nearly as much as his own plan, as long as the A’s stay in town. If Save Oakland Sports and other groups can come to a consensus on one site that has energy behind it and has been properly vetted, they have a shot. If they stand by the City’s current vision of multiple sites being equal with no real consensus, there’s nothing to rally behind. They’re just circles on a map. —– Note: As I was writing this in the middle of the night, I did not ask Dixon for permission to use his images. I apologize for that in advance, though I also cite fair use as this is a review.