Now that the London 2012 Games has ended, it’s time to reflect on how the Olympics were held there. We can also start to consider how the Games would be hosted in the Bay Area, should that come to pass.

The 80,000-seat Olympic Stadium was never going to match Beijing’s Bird’s Nest as a great architectural work, and it wasn’t designed to. The stadium was meant to be scaled back to 25,000 seats after its Olympic/Paralympic tenure. There were plans to use it as a soccer stadium for either Tottenham Hotspur or West Ham, but neither deal could be worked out.

According to GamesBids, the London buildout for the 2012 Games was $4 billion. You may remember that the Bay Area made its own bid for these very games a decade ago. The bid then was a mere $211 million, with few new competition venues as part of the plan. Instead, nearly $1 billion would’ve been budgeted for the Olympic Village, which would’ve been located at Moffett Field. Like many other bids, venues were to be grouped in clusters, with the main clusters being in San Francisco and at Stanford University.

Spread of Olympic venues in BASOC 2012 bid

Since the 2012 bid lost out to New York, much has changed in the Bay Area’s sports venue landscape. The earliest a Bay Area Games could occur is 2024 because the USOC is not bidding on the 2020 Games. A quick review of sports and venues in the 2012 bid:

- Athletics/Track and Field, Opening/Closing Ceremonies @ Stanford Stadium – A few years after the bid lost, John Arrillaga decided that it was time to revamp Stanford Stadium. The track and 36,000 seats were removed, making the new Stanford Stadium a compact, football/soccer venue. For any new Olympics bid, the Olympic Stadium would need to be located elsewhere – in the Bay Area.

- Soccer @ Candlestick Park, Oakland Coliseum, other stadia – Candlestick would be replaced by the 49ers Stadium in Santa Clara, whereas the Coliseum could be refurbished or be replaced by a new Raiders stadium. A new Candlestick was to be the centerpiece of a 2016 Olympic bid, but the 49ers never signed on and the bid died with the stadium. Stanford Stadium can now function solely as a soccer venue. The Earthquakes’ stadium could also be used as a secondary venue. This is one sport where the Bay Area is as strong as any worldwide in terms of hosting, though some games would be held in LA or San Diego (Stanford hosted some group and elimination games during the 1984 Summer Games).

- Baseball & Softball @ AT&T Park & Sunken Diamond – No longer needed since both sports are no longer Olympic events. That could change in the next decade or so.

- Boxing @ Cow Palace – By the time 2024 rolls around, the Cow Palace will be 83 years old with few renovations during that lifespan. It could remain a venue, or it may not be standing in a dozen years. If it’s still operational it’d be fine for boxing or one of the other arena sports such as handball, or as a backup basketball or volleyball venue.

- Basketball @ Oracle/Oakland Arena & Leavey Center/SCU – Whether or not the Warriors are still in Oakland, the arena is perfect for basketball and should stay a basketball venue. Leavey Center is somewhat small and should be replaced by either Maples Pavilion or Haas Pavilion. If built, a new waterfront SF arena could replace Oracle as the venue of choice, perhaps pushing volleyball to Oakland.

- BMX Racing @ N/A – BMX wasn’t an Olympic sport when bids were being accepted in 2002. It is now, and it shouldn’t be too difficult to figure out where it should go. Since the Olympics are held during the summer and building a BMX track requires moving a lot of dirt, it probably wouldn’t make much sense to put it in a baseball stadium since it would be highly disruptive. Either Spartan Stadium or Memorial Stadium could work, though both may have too many seats. A temporary venue may make more sense, or perhaps Kezar Stadium. If we’re looking at expanding facility, the Santa Clara PAL BMX track is a possibility. It would require expansion and the installation of seating.

- Cycling, Track @ Mather Park Velodrome, Sacramento – Plans originally called for a new mostly covered velodrome at Mather, a former Air Force Base. It’s another case where either a new temp-to-perm venue would have to be built, though it could conceivably go anywhere, not just Sacramento. Another planned site for a velodrome was Santa Clara, where the Soccer Park adjacent to the 49ers stadium/headquarters is located. The only other velodrome in the region is at Hellyer Park in San Jose, and it would require a major expansion to be Games-ready.

- Equestrian @ Monterey Horse Park – Located on the former Fort Ord, it’s a bit far from San Francisco but is much larger than Bay Area facilities such as the one in Woodside. An successful Games bid would probably provide enough money for the nonprofit group overseeing the Horse Park to get its vision completed.

- Field Hockey @ Spartan Stadium – The prospects for Spartan have only improved now that the stadium is using Field Turf instead of grass. Cal’s Memorial Stadium is also an option since it also uses artificial turf.

- Gymnastics @ HP Pavilion/San Jose Arena – There’s a long tradition of excellent support of gymnastics, up to and including this year’s Olympic trials. Unless the SF arena came into play, HP Pavilion should continue to be the gymnastics venue.

- Modern Pentathlon @ Maples Pavilion/Stanford – Shouldn’t change. Venues are in close proximity to each other.

- Swimming/Diving @ Stanford temporary facility – The Avery Aquatics Center at Stanford and the George Haines Int’l Swim Center in Santa Clara’s Central Park are both good facilities, but neither has the space for the 10,000 or so seats that would be needed in the future. Spieker Aquatics Complex at Cal barely has seats. This gives rise the the idea of a new swim center somewhere in the Bay Area with enough space to add temporary seats, the same way “wings” were added to London’s aquatic center.

- Tennis @ San Jose State South Campus – Fortunately, the Bay Area won’t have to follow up on London’s use of the Wimbledon and its world-beating facilities. Instead, it’s likely that Stanford’s Taube Tennis Center, which was expanded since the bid, would be used. Taube hosts an annual WTA tournament, but it lacks a really large stadium.

- Volleyball, Beach @ Edwards Stadium, Cal – I never understood this choice when the bid was released. You’d think that, unlike many Olympic cities, we have beaches, we’d want to host beach volleyball on the, well, beach. Here’s hoping that if a bid is made, a change is made to use either Ocean Beach or Santa Cruz Main Beach as the venue. The latter at least has the infrastructure to handle the event. If the Brits can make a beach volleyball stadium happen behind 10 Downing Street, we can certainly put a venue on a freaking beach.

- Volleyball, Indoor @ Haas Pavilion, Cal – No need to change things here. At 11,000+ seats, Haas is perfect.

- Water Polo @ George Haines Int’l Center – Would require temporary seating to double arena size to 5,000, the same size as the London temporary venue. Probably worth it. Stanford’s Avery Aquatics Center could also be used, though it too would require additional temporary seating.

- Weightlifting @ Henry J. Kaiser Convention Center, Oakland – With no budget money available to operate the venue, it seem like HJKCC would be ripe for the kind of investment needed to host weightlifting. Then again, the Bill Graham Civic Auditorium across the bay seems like just as good a fit and it wouldn’t require much work at all.

Other indoor events would be held either at Moscone Center or San Jose Convention Center, which makes sense given their flexibility and capacity.

New venues to be built

Without a large stadium with a track, the Bay Area would seem to be at a disadvantage compared to competing cities. Then again, maybe it’s not. The other American cities, Chicago and New York, also don’t have such stadia. Chicago’s bid was based on a temp-to-perm stadium to be built in Washington Park, near the University of Chicago on the South Side. New York’s 2012 bid was based on a Jets stadium on the West Side of Manhattan that got blown up by Cablevision, the company that also owns Madison Square Garden and the Knicks and Rangers. Houston and Philadelphia could also compete, but they’d have to build more venues than the Bay Area, Chicago, or NYC.

The Olympic stadium dilemma is simple. Track and field is only popular in most countries during the Olympics, making any large stadium with a track a white elephant. Even USC got rid of the track at the LA Memorial Coliseum to make it more football friendly, though it could in theory be converted back at some point. Since 2002, several undeveloped properties such as SF’s Mission Bay and San Mateo’s Bay Meadows have been developed, reducing the number of potential sites. Lennar still has a parcel for a stadium within its development footprint at Hunters Point, but that could disappear in time. Oddly enough, the best idea may be to float a stadium on barges in the bay. It could be docked next to the SF arena on Piers 30/32, and like Chicago’s stadium plan, could be built to have a permanent capacity of only 10,000. The Olympic capacity would be 80,000, almost all of it temporary. The low-profile permanent stadium could be floated around the Bay or even outside the Bay for other regions to use.

Moffett Field’s Olympic Village is a good concept in that it has plenty of space and is self-contained. It also has Google as a next-door neighbor to provide a huge amount of technological infrastructure if needed. Unfortunately, it’s not close to SF or many of the venues. Preferably, I would’ve liked to have seen Treasure Island used as the Olympic Village. As the Navy cleans up the land, developers are waiting to build new housing there as some of the last large development within SF city limits. Hunters Point could also work, but it’s already spoken for. Other possibilities include Alameda NAS, which would require new transportation infrastructure, and Golden Gate Fields.

An Aquatic Center has to be one of the big ticket items and is practically unavoidable. Santa Clara may be a possibility, but it’s plagued by numerous problems: limited space to expand, little parking, and its location right next to a residential neighborhood. A temp-to-perm facility would be best. From what I gather, there is only one pool that approaches Olympic size in all of San Francisco, inside the Koret Center at USF. There should be room for a facility somewhere in SF. If not, the East Bay or Peninsula may be good fits.

London put the BMX track and velodrome next to each other, which was a good move from a planning standpoint. Future cities may not have enough room to colocate the two sports in that manner, so it shouldn’t be a requirement. Either way, prep for both sports should be cheaper than the aquatic center or main stadium.

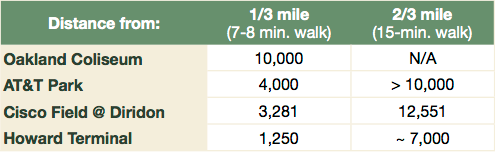

The issue that hurt BASOC in its 2012 bid was the geographical spread of the venues. The IOC prefers venues to be within 16 miles of each other with good transit links. In both cases, the Bay Area falls short. London made it work by putting venues right in the middle of the city and limiting the spread, even if it meant that the athletes often faced gridlock going to venues and the Olympic Village. Even though 2024 seems far away, it’s not likely that much of the needed public transit infrastructure being planned now (BART to Silicon Valley, High Speed Rail) will be completed by that point. And with some venues in far-flung places like Monterey or Folsom (rowing), accessibility will not be one of the bid’s strong suits. If anything, the IOC could be swayed by the need for fewer new venues, even temporary ones. A Summer Games in the Bay Area would be a crowning achievement for the region, and the political climate may have changed over the years to make the region’s plusses (available venues, lower cost, sustainability) even more important next time around.

P.S. – Not to be forgotten, Lake Tahoe and Reno are mulling a joint bid for the 2026 Winter Olympics.