As part of the expanded in-house audio coverage of the A’s, the team launched a new podcast covering ballpark matters. The first installment of The Build features A’s President Dave Kaval being interviewed by Chris Townsend. Included in the discussion is the following Kaval quote:

It’s just really important that people understand that we’re going to be responsible about environmental cleanup. That we’re going to take an industrial area and repurpose it just like San Francisco with AT&T Park or Oracle Park.

I’m sure this has been communicated to the various community groups the A’s are corresponding with. I hadn’t heard it quite so publicly stated until now.

I just wonder how effective this strategy will be.

Every time the A’s start on a new ballpark project, they encounter some sort of resistance. And without fail, that resistance tends to be minimized, only to eventually derail the A’s efforts. Or as Ken Arneson recently tweeted:

The script should be rather familiar by now. The A’s release news of a new site they’re interested in. Then someone mentions a process-related NIMBY issue in an article. The team says everything’s fine and everyone’s being heard, all while opposition mounts. Eventually the team moves on to the next dream site, sometimes scaling back the vision, sometimes expanding it. This happened at the Coliseum North site, then at Fremont, followed by San Jose, and finally the Peralta/Laney site. It’s practically like clockwork.

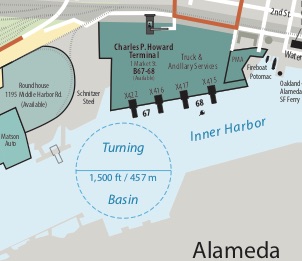

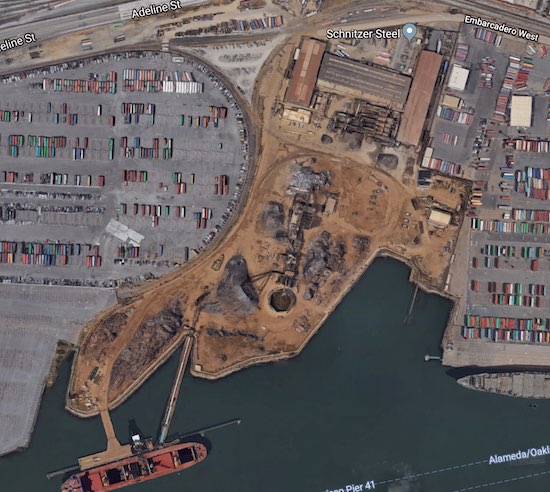

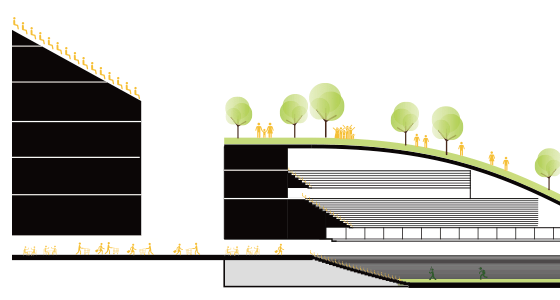

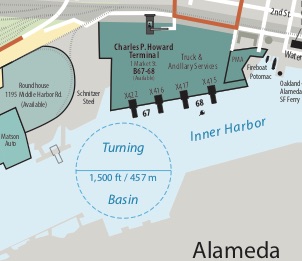

What concerns me is that the word you rarely hear in these public talks is the one word needed to forge a deal: compromise. It’s almost as if the strategy is that local government or a court will step in and rule for the A’s. There’s rarely any talk about how it could affect entrenched parties. I’ve heard a lot comments to the tune of, It’s hard but was it as hard as X? At this point, whether it’s harder than “X” is largely academic. If it’s hard enough to kill the project, that’s enough, and try as we might deign to understand the process, we can still have a very difficult time with those implications if we maintain blind spots. The one real effort to compromise with the Port pledged by the A’s so far is their willingness to remove several acres of land at Howard Terminal in order to expand the turning basin in the Inner Harbor. I’m surprised at how little press this has received so far, since it could significantly transform the shoreline along the Estuary and maritime uses. Schnitzer Steel could be affected as well, though how much isn’t clear.

Port interests have been upfront that redevelopment of Howard Terminal threatens their operations and livelihood. Perhaps that’s an overreaction, especially if the Port itself isn’t running at capacity. However, there is an argument that giving up shoreline from a purely commercial (real estate) interest is short-sighted.

About Kaval’s comment, I mentioned redevelopment last June when a fire at Schnitzer Steel broke out:

AT&T Park was made possible by the closure and decommissioning of the Embarcadero Freeway in San Francisco after Loma Prieta, which allowed the city to remake the entire waterfront from Mission Bay to Broadway.

The A’s aren’t asking to reform the Oakland waterfront the way the SF waterfront was redone after the earthquake. But if port interests feel threatened by even the hint of a transformation, you have to understand the history of the Port. The Oakland waterfront became a thriving industrial area thanks in part to San Francisco giving up industry on its inner bayside shoreline. Accessible shoreline for large ships and boats doesn’t grow on trees. Short-term concerns, such as impacts on heavy truck and rail traffic, have gotten vague suggestions for accommodation so far. Meanwhile, the Port continues to expand its operations thanks to its takeover and cleanup of the old Oakland Army Base.

Click to enlarge

In the map above, you’ll see that the Oakland shoreline is mostly divided into three zones. The maritime area, where traditional port operations take place, is in West Oakland. The commercial sector covers the Acorn neighborhood south of the 880-980 split through Jack London Square and out to Brooklyn Basin and Jingletown and East Oakland. The airport is its own economic engine. What we’re really talking about, then, is a sort of zoning turf war, with the commercial sector encroaching upon the maritime operations even as the maritime area itself expanded over the last twenty years.

That is the struggle the Port commissioners are dealing with. It may come to a head in the next few weeks, according to Port Commission President Ces Butner:

“It will be up to us to make a decision, both on the financial impact and on whether the ballpark fits in with the port,” Butner said. “We are not going to cause the terminals any financial hardships. We are not going to step on our own throat.”

Butner said a decision will be made hopefully by the end of April.

“Unlike politicians, we will not be kicking the can down the road,” he said.

Butner, who a couple years ago saved Speakeasy Brewing after the company shut down, could help determine the fate of another treasured Bay Area institution.