The late, long-lamented Key System once provided an efficient, well-planned streetcar network that operated in Oakland, Emeryville and Berkeley. In the wake of the Great American Streetcar Scandal, streetcar lines were replaced by buses. That led to the eventual development of the BART system, which in 1972 was a then-futuristic regional network that decidedly was not a streetcar replacement.

It helped somewhat that Oakland started as the heart of the BART network, with eight stations within city limits and the first main trunk line (Fremont-Richmond) running through Downtown Oakland. What remained was a hub-and-spoke system in which AC Transit buses fed newly established transit hubs at the BART stations. While buses had more route flexibility than streetcars, they lacked the permanence and service quality of streetcars or light rail.

60 years after the streetcar-to-bus debacle, the modern era of light rail passed by Oakland. Meanwhile, light rail proliferated in San Francisco in the 80’s and San Jose in the 90’s. The 21st century introduced BRT – light rail in terms of station infrastructure, but buses by motor and wheels.

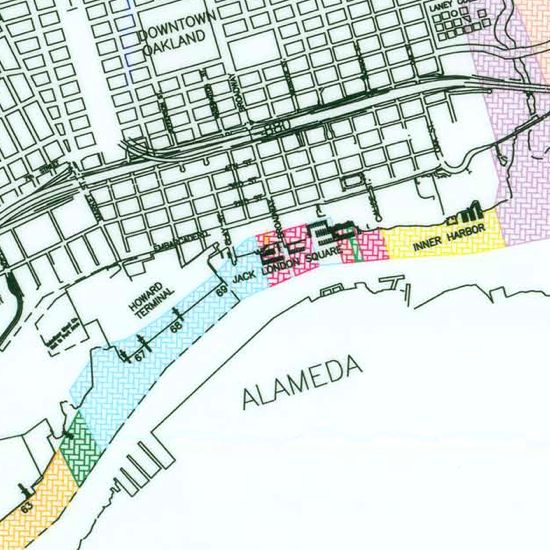

Construction continues apace on the San Pablo Ave and International Blvd lines. However, both terminate in or near Downtown Oakland, short of Jack London Square and Howard Terminal. Practically, that makes them no better than BART in terms of getting to the ballpark. If Howard Terminal becomes its own non-BART transit hub, it will be necessary for those BRT routes to extend to the waterfront. To accommodate BRT properly, at least one of the north-south streets running downtown (Broadway, Jefferson, Washington) will need to be modified to add BRT stations, eliminating parking or traffic lanes.

The free Broadway Shuttle provides a decent transfer option, though to properly handle the crush of pre-game and post-game riders transferring from BART, Broadway will still need to be modified. What could be the solution besides walking or street-clogging buses? A gondola, of course.

Wait. A gondola?

Saffron Blaze, via http://www.mackenzie.co

We’re not talking about the Venetian kind of gondola, as Oakland lacks the kind of canal system that could support a fleet of gondolas. Instead, the type of gondola discussed hangs in the air. Using similar technology as the Oakland Airport Connector, the gondola system the A’s are proposing would run above Washington Street between Jack London Square/Howard Terminal and 11th Street in Downtown Oakland.

Portland Aerial Tramway (via Tim Adams, flickr)

A scaled down gondola system was installed at the Oakland Zoo last year as part of the zoo’s California Trail expansion. Implementation was predicated on the notion that visitors should be able take the 1,780-foot span and 309-foot elevation change from the entrance to the new Landing Cafe at the California Trail; all while minimizing impact the wildlife beneath the gondolas. Gondolas tend to be reliable – zoo operational hiccup being an exception – and don’t use a lot of energy. Austrian vendor Doppelmayr, which also built the Airport Connector, claims that the system can carry 6,000 riders per hour. Neither of the American systems come anywhere close to approaching that capacity. Single lines in Bolivia and Colombia can carry 3-4,000 per hour. Those examples are among the busiest in the world.

The trip from the 12th Street/City Center BART station to Howard Terminal will run over flat land, though not without a transition. A rider disembarking from a Fremont or San Francisco-bound train will do so on the lowest level, the third subway deck beneath Broadway. From there fans have to take a two-story escalator, elevator, or stairs to the concourse level, walk towards the 11th Street exit, then take another escalator/elevator to street level. Once on the street, the fan would have to cross 11th Street to the Marriott City Center, then find a way to move past the hotel and up 5 floors to what is now the Warriors’ practice facility atop the Oakland Convention Center. From there there should be a gondola station that will whisk fans to Howard Terminal.

It’s not an elegant solution. It beats walking, right? While I’m sure Marriott would enjoy the uptick of baseball fans staying at the City Center hotel location, the company may not be so enthused at the idea of thousands of people not paying anything to trample the facility’s elevators. There will be many fans who decide it’s better to walk especially on a sunny day or take the Broadway Shuttle to the water. Others will have to herd like cattle up or down EIGHT flights to transfer From the subway to the gondola. A better solution may be for the City of Oakland to extend the station’s concourse level and build a separate exit from the BART station to the Convention Center that could include banks of escalators and elevators to navigate the other 5-6 levels.

(BTW the $1 million Warriors practice facility was thrown into the Coliseum Arena renovation deal. The City’s half of whatever settlement comes from the Warriors for breaking their lease could be put to good use once the remaining debt is paid off.)

Curiously, in 2007 the City of Hercules in Contra Costa County researched a gondola to help alleviate traffic on CA-4. It seemed somewhat outdated given recent advances in ropeway technology, but the basic tenets of the pro/con debate appear sound.

Advantages:

1. Capital costs are low. Aerial cable transit typically has the lowest capital cost (on a per mile basis) compared to other fixed-guideway technologies.

2. Operating and maintenance costs are low.

3. Environmental impacts are minimal. Cable systems leave only a small footprint, require little space for a guideway and towers, and can be easily retrofitted into existing streets.

4. Construction impacts are minimal. Except for a limited number of foundations for towers or terminals, much less site preparation is necessary than for other types of fixed guideway.

Disadvantages:

1. Expandability is impossible or difficult at best. Since current technology makes it difficult to have systems consisting of more than two stations, future expansion to other areas of the city may not be feasible.

2. Alignment tends to be limited to a straight line. Angle stations both increase costs and consume relatively large amounts of land, the latter being undesirable in urban areas. Concrete or steel guideways carrying self-propelled vehicles are preferable if a curved alignment is needed.

3. Availability, while high, is not as great as for other technologies.

4. High winds and electrical storms force shut downs which would not occur with other technologies.

5. Evacuation techniques are dramatic and unnerving. Cautious public officials are unlikely to feel comfortable with them. Although the techniques are proven safe

and effective, media may emphasize their dramatic aspect.

6. Insurance premiums are high. This tends to cancel advantages to low operating and maintenance costs.

Compared to other modes of transportation, there aren’t a lot of studies on gondolas in urban settings in the USA. There are successful examples of the technology in Portland (Portland Aerial Tram) and New York (Roosevelt Island Tramway). Yet the tech has had difficulty escaping the notion that it’s meant primarily for ski resorts. The Roosevelt Island Tramway may be the most apt comparison for a Howard Terminal Gondola, as it runs on a BART-like schedule and has cabins that can hold up to 125 people each. Newer cabins used in Vietnam can carry 200. That’s a lot more than cabins at the Oakland Zoo (8) or even Portland (78). My concern about the gondola is that with its limited availability it will be looked upon as an exclusive toy for the well-heeled. At least compared to the OAC it shouldn’t cost half a billion to build it.

And now there are rumblings that Howard Terminal could be just the thing to close down underutilized I-980, re-use the old Interstate right of way for both BART and high speed rail or Caltrain tracks, while offering a station at Howard Terminal AND offering the long-sought-after Southern Crossing via another Transbay Tube to reach San Francisco. This is a clear example of wishing for things with no regard to how much they cost. If the combined Howard Terminal ballpark and transit center and trains on 980 and expanded ferry service and water taxis and redesigned Oakland streets end up costing eleven figures, what’s a few billion extra among friends?

I asked Dave Kaval how the gondola would be operated. Would it have a separate fare, or something rolled into the ticket price? Kaval response was

That’s not really determined yet. There’s an operating agreement with the operator (Doppelmayr or Garaventa), then we work out the details from there including fares.

Presumably that would include integration with the Clipper Card system, though BART saw fit to create its own app to handle payments for the Airport Connector as well.

My friends, Jeffrey and Kevin August, walked from the 12th Street City Center BART station to the open house at the A’s Jack London Square headquarters. They’re planning to do at least one more trip including Lake Merritt, then I plan to join them for the walk when FanFest happens, weather permitting.

Look, we all know how much of a cluster the Bay Area’s transit situation is. Could we all get on the same page and set some priorities? A fanciful double-tunnel based on a non-existent train extension incumbent upon a mega-development based on a small ballpark that is far from being approved? Pardon me for thinking it’s a bit of a stretch. Oakland is blessed to be the heart of the BART system. Why spend so much effort dreaming of ways to avoid BART? Or why does a second Transbay Tube have to connect through Oakland when there are so many other communities that don’t have BART at all? Answers to many of these questions will be revealed in the forthcoming EIR.